The Northern Liberties neighborhood in north Philadelphia is experiencing a renaissance. The fusion of an improved retail district, fashionable bars and restaurants, and a growing population are contributing to the renewal of this community. Young residents, artist types, and families are increasing the vibrancy of the sidewalks. Commercial spaces continue to spring up in the area, and Liberty Lands, a community garden, park, and playground, is recognized for its seasonal lawn-chair drive-in movie.

This success, however, does not come without burden. Real-estate developers and speculators can sense a lucrative opportunity like a shark smelling blood, and developer interests often fail to acknowledge the vision of the community. Northern Liberties is no exception. Plans for large-scale artist communities and New York style lofts will upset forever the fabric of this close-knit, affordable community. And with new construction comes high prices, potentially pricing out the artists that transformed this community from blight to rebirth.

One developer stands alone in his ability to profoundly impact Northern Liberties. That man, Bart Blatstein, president of Tower Investments, owns 12% of the neighborhood’s property. An outfit primarily known for building retail and commercial properties, Tower is responsible for some of the most heinously designed strip malls in Philadelphia. But Tower Investments prides itself on finding opportunity in areas overlooked and underserved by more traditional firms. To his credit, Blatstein found a niche in developing land long forgotten by the city, restoring former industrial wastelands into utilized commercial districts.

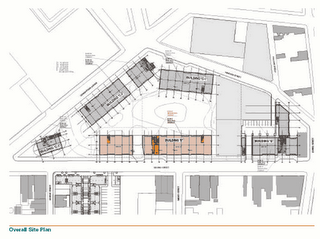

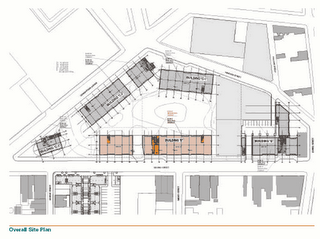

The most anticipated of Tower Investments' projects in Northern Liberties is the development of the Piazza, designed by architects Scott Erdy and David McHenry. In the beginning stages of construction, this planned “artist’s community” sits on a three-acre portion of the 12-acre Schmidt’s Brewery site, and is marketed as a community within a community: 538 apartments, 124 townhouses, a 700-car parking garage, and more than 200,000 square feet of commercial space. The focal point of the Piazza will be an open public space, fulfilling Blatstein's vision of recreating the Italian piazzas, which will be fronted by shops, galleries and restaurants. An oval-shaped, seven-story glass structure for office space will be constructed at the northern tip of the complex, and will be the tallest building in the immediate area. The sleek glass tower demands attention, sending a clear message to the city that Northern Liberties has emerged, renewed.

Many of the Erdy McHenry designs are bulky and width-oriented, stressing the horizon. The design demands substantial space consisting of many acres, and they get it here. In terms of width, the design communicates with the city's endless blocks of two and three-story row homes. But this project is bulkier than any other structure in the neighborhood. The massive rectangles are softened by the adjacent seven-story tower. When viewed collectively, however, this project is gargantuan and fails to fit in with the tidy, grid pattern of the city.

Furthermore, the internal feel that the Piazza perpetuates is troubling when one considers the surrounding area. The complex walls shield the interior, creating an impenetrable shell protecting residents from blight just to the north. It equates to a business campus, or a college dormitory complex. Perhaps this is the designer’s way of referencing the structures that once graced the site: massive warehouses. But this is also Blatstein manifesting his vision of an artists’ community. The design would be great for an addition to the Fashion Institute of Technology.

The complex also fails to incorporate one of the hallmarks of New Urbanism: connectivity. The huge plot of land, coupled with the sealed-off complex, makes it impossible for pedestrians to navigate. The lack of connections from one side of the complex to the other will have a negative impact on the street's vibrancy in certain areas. Plainly stated, people are going to have a difficult time getting around this thing. The plot should have been cut in half down the center, creating a new street and sidewalks. Yes, it is oddly shaped and obstructs the grid, but this tract is easier to digest had it been cut into two quadrants. Allowing pedestrians to shortcut through the Piazza to get from one side of the complex to the other is an option that must be clearly presented. The creation of a new street and sidewalk could have remedied this problem, opening up the complex to invite its surroundings.

The name of the complex, Piazza, is misleading. It remains to be seen if the open space at the center of the complex will be utilized as a public space. Judging from early renderings, the space resembles an internal sculpture garden or quad, inviting only to the inhabitants of the community. The paths from the existing grid into the complex are nebulous and it is difficult to make out any wide corridors, creating a closed-off complex that is uninviting to non-residents. This seems to contradict the historical definition of a piazza, which comes from the Latin platea, meaning broad street. The missing element here is accessibility and openness. Also, the popularity of the piazza will depend on the inviting nature of the space surrounding the seven-story office tower. The tower itself acts like a “gatekeeper,” preventing a clear path into the complex. But if the developer can incorporate retail, restaurants, and outdoor seating at the base of the business tower, this open space may potentially direct pedestrians into the Piazza.

While the creation of ground-level retail, shops, galleries and restaurants will ultimately benefit the Northern Liberties community, such amenities should also seek to benefit the surrounding neighborhoods. A new development, with high rents designed in such a manner as to shield itself from the outside world, may become self-serving. This fact is implicit within the design, and one hopes that the architect and developer find a way to reach out to the neighboring communities. The retail district will certainly increase the street's vibrancy. But the question remains whether this enthusiasm can spread into the contiguous areas that are also in need of amenities. With so many services instantly provided to them, new residents may feel less-inclined to diverge from the safe, cozy surroundings that the Piazza provides. Departure from the development should be encouraged by including new and already existing businesses just outside of Northern Liberties.

Last weekend I hopped on a bus tour sponsored by Friends of the High Line. Our destination was the former Fresh Kills landfill, on Staten Island, NY. The tour was provided by the New York City Parks and City Planning Departments, which did a solid job explaining the intense process of converting a 3,000 acre landfill into a park flowing with green grass, wildlife, and eventually people, yes, people. Lots of them.

But how does one even begin to transform a place that for 53 years was the dumping ground for New York City’s garbage? The landfill, opened by Robert Moses (we can't seem to dodge this guy) in 1947, received at its peak an average of 11,000 tons of residential and commercial garbage per day. The technology and resources needed to transform an environmental wasteland to an environmental gem are daunting, and one would guess there are countless environmental and health concerns. To ensure the environmental security of the site, Fresh Kills will undergo both the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) and State Environmental Quality Review (SEQRA). The environmental review process will analyze the various proposed changes to the park, along with the possible affects on the exposed public, wildlife, and surrounding environment. The various other controls that will be implemented include methane gas control, which the City harvests and sells; leachate collection and treatment, which is the liquid byproduct of the trash decomposition; and a post-closure operation and maintenance plan for a 30-year period, all enforced by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC).

Fresh Kills Park has become one of the jewels of Mayor Bloomberg's crown. The City and Field Operations, (a private design firm and winner of the competition to design Fresh Kills Park) along with scores of other stakeholders, have created an oasis-like vision for the former dump, and includes 2,315 acres of park land with open public spaces, athletic facilities, field houses, and commercial uses. What is most ironic are plans for revitalizing the natural landscape of the site. Fresh Kills Park will build upon the area’s rich environmental history, a difficult thought given the site's reputation as the world’s largest landfill.

Last weekend I hopped on a bus tour sponsored by Friends of the High Line. Our destination was the former Fresh Kills landfill, on Staten Island, NY. The tour was provided by the New York City Parks and City Planning Departments, which did a solid job explaining the intense process of converting a 3,000 acre landfill into a park flowing with green grass, wildlife, and eventually people, yes, people. Lots of them.

But how does one even begin to transform a place that for 53 years was the dumping ground for New York City’s garbage? The landfill, opened by Robert Moses (we can't seem to dodge this guy) in 1947, received at its peak an average of 11,000 tons of residential and commercial garbage per day. The technology and resources needed to transform an environmental wasteland to an environmental gem are daunting, and one would guess there are countless environmental and health concerns. To ensure the environmental security of the site, Fresh Kills will undergo both the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) and State Environmental Quality Review (SEQRA). The environmental review process will analyze the various proposed changes to the park, along with the possible affects on the exposed public, wildlife, and surrounding environment. The various other controls that will be implemented include methane gas control, which the City harvests and sells; leachate collection and treatment, which is the liquid byproduct of the trash decomposition; and a post-closure operation and maintenance plan for a 30-year period, all enforced by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC).

Fresh Kills Park has become one of the jewels of Mayor Bloomberg's crown. The City and Field Operations, (a private design firm and winner of the competition to design Fresh Kills Park) along with scores of other stakeholders, have created an oasis-like vision for the former dump, and includes 2,315 acres of park land with open public spaces, athletic facilities, field houses, and commercial uses. What is most ironic are plans for revitalizing the natural landscape of the site. Fresh Kills Park will build upon the area’s rich environmental history, a difficult thought given the site's reputation as the world’s largest landfill.

Is it any wonder that a project of this magnitude would take place in New York City? Of course you can argue that no other City in the U.S. would need a 3,000 acre landfill. But the Bloomberg Administration has sustained its axiom that there is no project too big. He and his administration continue to push the limits with bold ideas.

Is it any wonder that a project of this magnitude would take place in New York City? Of course you can argue that no other City in the U.S. would need a 3,000 acre landfill. But the Bloomberg Administration has sustained its axiom that there is no project too big. He and his administration continue to push the limits with bold ideas.